This article is intended for general informational and educational purposes and does not provide medical, legal, or professional advice.

What Are “Criteria Pollutants” in Air Quality Research

Definition and Origin of the Term

In air quality research and regulation, the term criteria pollutants refers to a defined group of air pollutants that are routinely monitored and assessed using standardized scientific and administrative criteria. The designation originates from regulatory and monitoring frameworks in which certain pollutants are selected based on their widespread presence in ambient air, the availability of reliable measurement methods, and the existence of a sufficient scientific record to support systematic observation.

The term does not emerge from atmospheric chemistry alone. Instead, it reflects the intersection of scientific knowledge and institutional practice, where pollutants are identified for routine monitoring because they can be consistently detected and reported across locations and time periods.

This usage aligns with definitions employed by international and national institutions such as the World Health Organization (WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines) and India’s Central Pollution Control Board (National Ambient Air Quality Standards).

Criteria Pollutants as an Operational Classification

Criteria pollutants are not defined by a shared chemical structure or a single physical property. Rather, they are grouped because they function as operational indicators within air quality assessment systems. This means that the category is designed to support observation, comparison, and reporting, rather than to provide an exhaustive classification of all substances present in the atmosphere.

By focusing on pollutants that are commonly observed in outdoor air and measurable using standardized instruments, this classification enables institutions to generate comparable datasets. As a result, the term criteria pollutants is best understood as a functional construct that facilitates monitoring and data interpretation, rather than a theoretical model of atmospheric composition.

Comparability and Standardization in Air Quality Monitoring

A central purpose of identifying criteria pollutants is to enable comparability across regions and time periods. Standardized definitions allow pollutant concentrations to be tracked using common reference points, making it possible to examine patterns and variability without requiring identical environmental conditions.

This emphasis on comparability explains why criteria pollutants are defined using clear physical or chemical parameters—such as particle size thresholds or molecular identity—rather than more complex descriptors. The classification prioritizes consistency and reproducibility, which are essential for long-term monitoring systems.

Scope and Limitations of the Category

The list of criteria pollutants does not encompass all air contaminants present in the atmosphere. Numerous other substances, including volatile organic compounds, air toxics, and region-specific pollutants, may be detected in ambient air but are not included in this category. Their exclusion does not imply lesser significance; rather, it reflects differences in monitoring practices, measurement feasibility, or regulatory history.

The composition of criteria pollutant lists may also vary slightly between countries. Such variation is generally shaped by differences in monitoring infrastructure, environmental context, and historical development of air quality frameworks. Despite these differences, the underlying principle—selecting pollutants that can be routinely and reliably measured—remains consistent.

Commonly Designated Criteria Pollutants

Within this framework, particulate matter (PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀) and selected gaseous pollutants (NO₂, SO₂, and O₃) are commonly designated as criteria pollutants. Each is defined using specific physical or chemical characteristics that enable consistent identification and measurement within ambient air monitoring systems.

These pollutants are treated as reference categories through which broader air quality conditions are observed and documented within air pollutant classification frameworks. Their inclusion reflects measurement practicality and standardization rather than an attempt to represent the full complexity of atmospheric mixtures.

Particulate Matter as a Pollutant Category (PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀)

Defining Particulate Matter in Atmospheric Science

Particulate matter refers to a heterogeneous mixture of solid particles and liquid droplets suspended in the air. These particles vary widely in size, shape, density, and chemical composition and may include materials such as dust, soot, smoke, or microscopic liquid aerosols. In atmospheric science, particulate matter is not treated as a single substance but as a collective category encompassing a broad range of particle types.

Because of this heterogeneity, particulate matter cannot be classified meaningfully using chemical composition alone. Instead, atmospheric research relies on physical characteristics, particularly particle size, as the primary basis for classification. Particle size influences how particles remain suspended in air, how they are transported, and how they can be captured by monitoring instruments.

Aerodynamic Diameter as a Classification Principle

The size of a particle in air quality research is described using its aerodynamic diameter. This measure reflects how a particle behaves as it moves through air, rather than its exact geometric dimensions. Aerodynamic diameter accounts for factors such as particle shape and density, allowing particles with different physical forms to be compared within a single classification system.

This approach enables consistent categorization across diverse particle populations. By focusing on aerodynamic behavior, atmospheric science applies a practical abstraction that aligns particle classification with the operating principles of air sampling instruments. As a result, particulate matter categories are defined operationally, based on how particles interact with airflow during measurement.

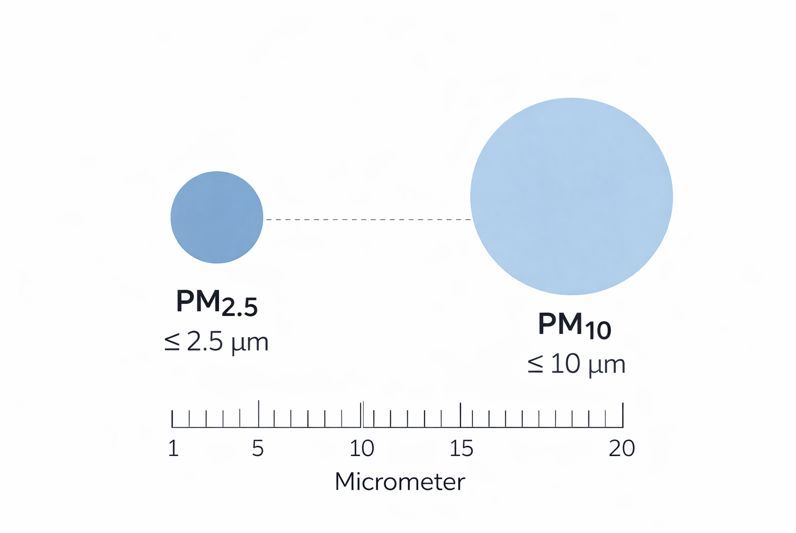

PM₂.₅ — Fine Particulate Matter

PM₂.₅ refers to particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 micrometres (µm) or smaller. These particles are described as “fine” because they are not visible to the naked eye and tend to remain suspended in the air for extended periods. In air quality monitoring systems, PM₂.₅ is treated as a distinct category due to its clearly defined size range and its consistent detectability across different environments.

Size-based particulate classifications are used consistently across global air quality monitoring frameworks, including those outlined in WHO air quality guidelines and India’s National Ambient Air Quality Standards.

The definition of PM₂.₅ is strictly size-based. It does not specify chemical composition, emission source, or formation mechanism. Consequently, PM₂.₅ includes particles with diverse physical and chemical properties, unified only by their ability to pass through size-selective sampling inlets designed for this category. This reflects the broader principle that particulate matter classifications prioritize measurable characteristics over compositional detail.

PM₁₀ — Coarse Particulate Matter

PM₁₀ includes particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of up to 10 micrometres. This category encompasses both fine particles (including PM₂.₅) and larger, coarse particles. In practical monitoring contexts, PM₁₀ measurements are often interpreted as representing particles in the approximate size range between 2.5 µm and 10 µm, although the formal definition includes all particles below the 10 µm threshold.

Coarse particles tend to settle more rapidly than finer particles and are more influenced by localized physical conditions such as wind or surface disturbance. As with PM₂.₅, PM₁₀ is defined solely by size criteria rather than by composition. This means that the PM₁₀ category may contain a wide variety of particle types that share no common chemical characteristics beyond their aerodynamic behavior.

Particulate Matter Categories as Measurement Constructs

PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀ are best understood as measurement constructs rather than discrete physical entities. The boundaries between these categories are determined by the design and performance of monitoring instruments, which apply size-selective cut-offs to incoming air samples. These cut-offs create operational thresholds that allow particles to be grouped consistently across monitoring networks.

Because these thresholds are instrument-dependent, they represent practical compromises rather than absolute physical divisions in the atmosphere. Particles near size boundaries may be classified differently depending on measurement conditions, a limitation that is widely acknowledged in atmospheric science literature.

Why Particle Size Is Central to Classification

Size-based classification remains central to particulate matter definitions because it provides a reproducible and standardized basis for observation. Particle size determines how particles are transported in air and how they are captured by monitoring equipment, making it a critical parameter for consistent measurement.

At the same time, reliance on size introduces inherent limitations. Particles of similar size may differ substantially in composition, origin, and structure, and size alone does not convey information about these attributes. Nevertheless, size-based categories such as PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀ continue to serve as foundational reference classes within air quality research because they balance scientific abstraction with measurement feasibility.

Gaseous Criteria Pollutants: NO₂, SO₂, and O₃

Gaseous Pollutants in Ambient Air Classification

Gaseous criteria pollutants are defined as individual chemical species present in ambient air that can be reliably detected and quantified using standardized analytical methods. Unlike particulate matter, which is classified primarily by physical size, gaseous pollutants are delineated by molecular identity and detectability. This approach allows specific gases to be monitored independently, even when they coexist with chemically related compounds in the atmosphere.

The classification of gaseous criteria pollutants reflects monitoring practice rather than a comprehensive grouping of all atmospheric gases. Each pollutant is treated as a distinct category based on its measurable properties and its suitability for routine observation within air quality monitoring systems.

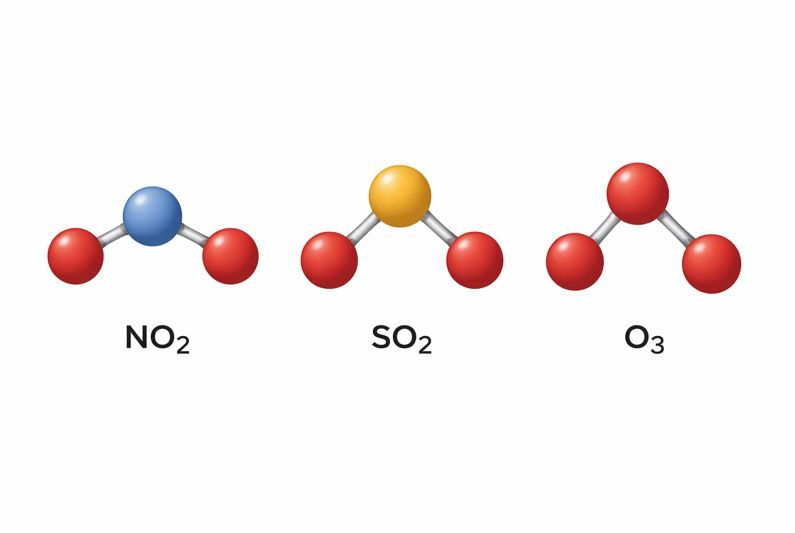

Nitrogen Dioxide (NO₂): Chemical Identity and Indicator Status

Nitrogen dioxide is a gaseous compound composed of nitrogen and oxygen atoms. In air quality research, NO₂ is defined by its molecular structure and characteristic spectroscopic properties, which enable it to be detected and quantified in ambient air using continuous monitoring instruments. These properties allow NO₂ to be identified as a discrete chemical species rather than as part of a broader chemical mixture.

Although nitrogen oxides are often discussed collectively in atmospheric science, the definition of NO₂ as a criteria pollutant does not extend to other nitrogen oxide compounds. This distinction reflects analytical practice: NO₂ can be measured independently with a high degree of consistency, whereas other nitrogen oxides may require different detection approaches or are grouped differently depending on context. As a result, NO₂ is treated as a separate reporting category within monitoring frameworks.

Sulfur Dioxide (SO₂): Molecular Specificity in Monitoring Frameworks

Sulfur dioxide is a colorless gaseous compound consisting of sulfur and oxygen atoms. In atmospheric science, SO₂ is defined by its molecular composition and distinct absorption characteristics, which allow it to be identified as a standalone pollutant in ambient air. These properties support its routine measurement across a range of monitoring environments.

The definition of SO₂ as a criteria pollutant is based on measurable concentration rather than on chemical grouping. Other sulfur-containing compounds may be present in the atmosphere but are not included within the SO₂ category unless they are explicitly defined and monitored separately. This highlights the principle that gaseous criteria pollutants are delineated according to analytical separability, not chemical family membership.

Ozone (O₃): Location-Based Definition in Air Quality Research

Ozone is a molecule composed of three oxygen atoms and occurs naturally at different altitudes in the atmosphere. In air quality research, the term ground-level ozone refers specifically to ozone present in the lower atmosphere, where it is monitored as an air pollutant. This locational distinction is central to how ozone is defined within ambient air monitoring frameworks.

Unlike many other gaseous pollutants, ozone is classified based on its presence and concentration at ground level rather than on direct emission characteristics. Its designation as a criteria pollutant therefore reflects where it is observed and measured, not a general categorization of ozone across all atmospheric layers. This reinforces the operational nature of pollutant definitions within air quality systems.

Conceptual Differences Among Gaseous Criteria Pollutants

Although NO₂, SO₂, and O₃ are all gaseous pollutants, they differ in chemical stability, reactivity, and persistence in ambient air. These differences influence how each gas is detected, monitored, and reported within air quality systems. Measurement techniques and reporting conventions are adapted to account for these distinct properties.

Despite these differences, the basic definitions of gaseous criteria pollutants remain grounded in chemical identity and detectability. Each pollutant is treated as a discrete observational category, selected for its suitability for standardized monitoring rather than for its role in broader atmospheric processes. This approach ensures consistency in classification while acknowledging underlying chemical diversity.

How These Pollutants Are Defined Across Scientific and Institutional Frameworks

Scientific Conventions and Institutional Requirements

Definitions of criteria pollutants are shaped by an interaction between scientific conventions and institutional requirements. Scientific definitions prioritize observable physical or chemical characteristics, such as particle size for particulate matter or molecular structure for gaseous pollutants. These characteristics provide a stable basis for identifying pollutants as distinct entities within the atmosphere.

Institutional definitions build upon this scientific foundation while incorporating practical considerations related to routine monitoring. Factors such as instrument capability, data comparability, and reporting consistency influence how scientific concepts are translated into standardized pollutant categories. As a result, pollutant definitions reflect both theoretical understanding and operational feasibility.

Concentration-Based Metrics and Standardized Reporting

Across global air quality frameworks, criteria pollutants are defined and compared using concentration-based metrics. These metrics express the amount of a pollutant present per unit volume or mass of air, providing a common quantitative reference for observation and documentation. Concentration-based definitions allow data collected in different locations or time periods to be assessed using consistent units.

Formal definitions often incorporate averaging periods, such as hourly or daily concentrations. These temporal components are introduced to standardize reporting and reduce variability associated with short-term fluctuations. Importantly, averaging periods are measurement conventions rather than intrinsic attributes of the pollutants themselves; they shape how data are recorded without altering the underlying definition of the pollutant.

National Frameworks and Contextual Adaptation

At the national level, pollutant definitions generally align with international scientific conventions while reflecting local monitoring systems and environmental contexts. In India, national institutions adopt criteria pollutant definitions that are broadly consistent with global frameworks, enabling comparability with international datasets.

At the same time, definitions may be adapted to reflect the structure and coverage of national monitoring networks. Such adaptation does not alter the core conceptual basis of pollutant classification but ensures that definitions remain applicable within existing institutional and technical capacities. This illustrates how standardized concepts are implemented within diverse observational contexts.

Methodological Limits and Operational Boundaries

Criteria pollutant definitions are subject to methodological limits imposed by measurement technologies. Monitoring instruments apply size cut-offs, detection thresholds, and sensitivity limits that influence how pollutants are categorized and reported. These constraints are inherent to observational systems and shape the practical boundaries of pollutant definitions.

For particulate matter in particular, size thresholds such as 2.5 µm or 10 µm represent operational standards rather than sharp physical divisions in the atmosphere. Particles exist along a continuous size spectrum, and classification boundaries are introduced to support consistent measurement rather than to reflect discrete natural categories. This limitation is widely acknowledged in atmospheric science literature.

Definitions as Tools for Observation and Analysis

Taken together, these factors underscore that criteria pollutant definitions function as tools for systematic observation and analysis. They provide structured ways to organize complex atmospheric information into measurable categories while recognizing that no single framework can fully capture atmospheric variability.

By emphasizing standardization, comparability, and measurement feasibility, scientific and institutional frameworks enable pollutants to be defined in ways that support long-term monitoring and research. These definitions are best understood as analytical constructs that balance scientific abstraction with practical observation.

Conclusion

Criteria pollutants such as PM₂.₅, PM₁₀, NO₂, SO₂, and O₃ are defined within air quality research as standardized categories intended to support the systematic observation and comparison of ambient air conditions. Their classification is based on measurable physical or chemical characteristics—most notably particle size for particulate matter and molecular identity or location for gaseous pollutants—rather than on sources, effects, or outcomes.

The concept of criteria pollutants reflects an operational framework rather than a comprehensive description of atmospheric composition. These pollutants are grouped because they are widely observed in ambient air, can be monitored using established and repeatable methods, and are reported consistently across scientific and institutional systems. As documented in atmospheric science literature, such definitions are shaped by measurement technologies, analytical conventions, and institutional practice, which introduces acknowledged boundaries and uncertainties, particularly for size-based particulate matter categories.

Within Phase 1, the focus remains on clarifying what these pollutants are and how they are defined, rather than on how they behave, vary, or are interpreted in applied contexts. This definitional foundation provides the conceptual structure upon which later examination of measurement practices, spatial and temporal patterns, and broader interpretive frameworks can be built in subsequent phases.

GreenGlobe25 Editorial Team

This article was prepared by the editorial team at GreenGlobe25, an independent educational platform focused on environmental governance, pollution monitoring systems, and sustainability-related research. Content published on GreenGlobe25 is developed as part of an educational research initiative and is based on publicly available government publications, institutional reports, and peer-reviewed academic literature.

The editorial process emphasizes descriptive analysis, methodological clarity, and accurate representation of source material. Articles are reviewed internally to ensure alignment with institutional data, neutral framing, and clear distinction between documented observations and interpretation.

Content is intended for general informational and educational purposes only. It does not provide medical, legal, policy, or professional advice, and does not recommend specific actions or interventions.

References

- World Health Organization

WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide. WHO, Geneva. - Central Pollution Control Board

National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). Government of India. - Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change

National Air Quality Monitoring Programme (NAMP) documentation. - United Nations Environment Programme

Air Pollution in Asia and the Pacific: Science-Based Solutions. - Seinfeld, J. H., & Pandis, S. N.

Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change.