This article focuses on air pollution standards, with brief references to noise and water limits included only for institutional comparison.

Introduction

In India, pollution is rarely discussed without numbers. Headlines frequently cite Air Quality Index values, noise limits expressed in decibels, or water quality readings drawn from official monitoring reports. These figures are often treated as direct indicators of environmental conditions, yet the standards behind them are not always clearly understood.

Two institutions are most commonly referenced in this context: India’s Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) and the World Health Organization (WHO). CPCB standards function as national institutional reference points that guide environmental monitoring and reporting within India. WHO guidelines, by contrast, are global reference values developed through international scientific assessments and are intended to support comparative understanding across regions. Each operates within a distinct institutional and legal framework.

This article explains how Indian pollution standards are defined, how CPCB limits differ from WHO guideline values, and why those differences exist, without ranking one as better or worse. The purpose is not to evaluate policies, but to clarify how environmental numbers are framed, interpreted, and used in reporting contexts.

For a broader discussion of air pollution causes, impacts, and governance context, see the main air pollution overview.

Pollution standards vary according to institutional context, monitoring coverage, and policy objectives. Recognizing these distinctions allows pollution data to be read with clarity rather than confusion, grounded in institutional design, scientific assessment, and real-world conditions.

While this explainer focuses on air pollution standards, references to noise and water limits are included only to illustrate how institutional frameworks differ across environmental domains.

TL;DR

- Pollution standards are reference tools, not guarantees of safety or predictions of individual health outcomes.

- In India, pollution is regulated using standards set by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), which guide monitoring and reporting.

- World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines provide global, science-based reference values and are advisory rather than legally enforceable.

- Differences between CPCB limits and WHO guideline values reflect institutional context and policy objectives, not simple “better or worse” judgments.

- Understanding how these standards are used helps readers interpret pollution data accurately and in context.

Why Pollution Standards Exist

Pollution standards exist to provide a shared reference framework for describing environmental conditions in a consistent and comparable way. Many forms of pollution—such as fine airborne particles, ambient noise, or water quality characteristics—are not directly perceptible without measurement. Standards translate these complex or invisible phenomena into defined indicators that can be observed, recorded, and communicated across different locations and time periods.

In India, pollution standards are defined through national institutional frameworks coordinated by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) These standards establish how environmental measurements are categorized and reported within official monitoring systems. They shape the way data from monitoring networks is aggregated, summarized, and presented, including through commonly used indicators such as air quality indices or designated noise categories. In this sense, standards function as reference structures that support comparability rather than as direct statements about environmental conditions.

At the international level, organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) publish guideline values derived from large bodies of scientific assessment. These guidelines are intended to summarize evidence and provide a common reference for understanding environmental indicators across countries and regions. Unlike national standards, WHO guidelines are advisory in nature and do not carry institutional status within domestic monitoring systems.

Pollution standards are therefore best understood as tools for consistency rather than guarantees of safety or predictions of individual outcomes. They are shaped by scientific assessment, measurement capability, and institutional context, and are designed to support structured interpretation of environmental data. Recognizing the purpose of these standards helps readers interpret pollution figures as reference points within monitoring systems, rather than as absolute judgments about environmental quality.

CPCB Pollution Standards in India – An Overview

In India, pollution standards are developed and coordinated through institutional frameworks associated with the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), a statutory body under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. These standards define how different forms of pollution are described, measured, and reported within national environmental monitoring systems. Their primary function is to establish consistent reference points that allow environmental data to be collected and compared across locations and over time.

CPCB standards extend beyond numerical limits alone. They specify classification systems, averaging periods, and reporting categories that shape how monitoring data is organized and communicated. In this way, the standards function as structured descriptors within institutional datasets, supporting comparability rather than serving as direct indicators of environmental conditions.

Scope and Function of CPCB Standards

CPCB pollution standards operate as national reference frameworks within environmental monitoring programs. They are used to define how observations from monitoring networks are grouped, summarized, and presented in official records and public datasets. While the application of these standards involves multiple institutions, the standards themselves provide a common structure that allows data from different regions to be interpreted within a shared framework.

The design of CPCB standards reflects the need for consistency across varied geographic and environmental contexts, including urban, industrial, rural, and ecologically sensitive areas. Their role is to support uniform description and reporting, rather than to evaluate conditions or outcomes.

Major Pollution Categories Covered by CPCB

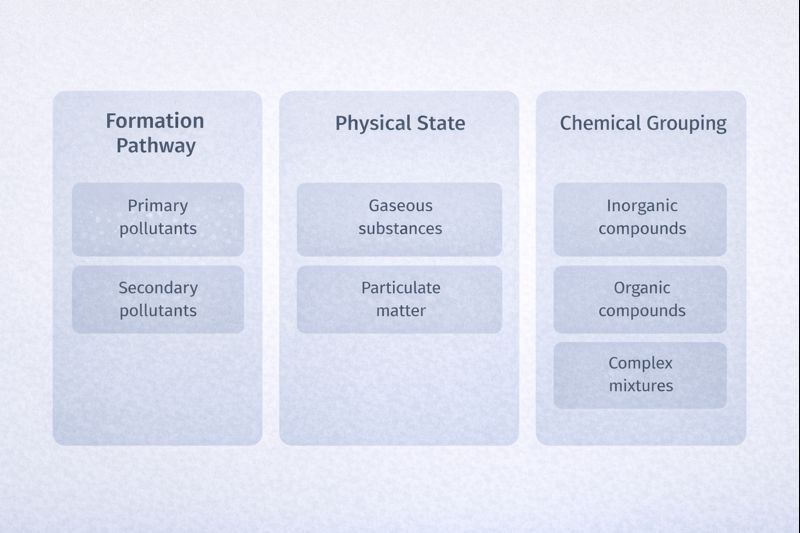

CPCB standards address several categories of environmental observation, each with its own measurement logic and reporting conventions.

Air pollution

National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) define reference concentration values for key ambient air pollutants such as particulate matter (PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀), nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, ozone, and carbon monoxide. These values are expressed using standardized averaging periods, including annual and short-term intervals, to support consistent reporting and comparison across monitoring locations.

Noise pollution

Noise standards classify areas into designated zones, including residential, commercial, industrial, and silence zones. Each zone is associated with defined sound level ranges for daytime and nighttime periods. These classifications provide a common framework for describing ambient noise conditions within different land-use contexts.

Water pollution

Water quality standards describe parameters used to characterize surface and effluent water conditions, such as pH, turbidity, temperature variation, and dissolved constituents. These parameters are organized into reporting categories that support structured observation of water bodies and designated use classifications.

Interpretive Context

Across all categories, CPCB pollution standards are best understood as descriptive reference systems. They define how environmental measurements are structured within official datasets, rather than serving as judgments about environmental quality or predictors of specific outcomes. Their role is to enable consistent monitoring and communication of environmental information within India’s institutional context.

How CPCB standards are applied in practice

CPCB standards are applied within environmental monitoring systems to structure how pollution data is collected, processed, and presented. Measurements recorded at monitoring stations are organized using defined parameters, averaging periods, and classification rules before being incorporated into official datasets. This process allows observations from different locations and time intervals to be reported in a consistent and comparable format.

Within these systems, raw measurements are typically aggregated and summarized to support standardized reporting outputs. These may include periodic reports, publicly accessible datasets, or composite indicators that present environmental information in a structured form. The role of CPCB standards in this context is to define how data is grouped and described, rather than to assess individual exposure or predict specific outcomes.

CPCB standards are periodically reviewed to reflect developments in scientific assessment methods, measurement techniques, and data availability. Changes to standards generally involve adjustments to classification logic, reporting conventions, or parameter definitions, rather than reinterpretation of observed conditions.

Understanding CPCB standards as components of a monitoring and reporting framework—rather than as absolute indicators of safety or risk—provides essential context for examining how national standards differ from international guideline values developed for comparative reference.

These details are included only to explain institutional context, not to evaluate policy performance.

WHO Environmental Guidelines – A Global Reference Point

National pollution standards and international environmental guidelines serve distinct but complementary roles. While national agencies define standards within specific institutional systems, global organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) develop guideline values intended to function as scientific reference points across countries and regions. These guideline values are published in WHO documents, including the Global Air Quality Guidelines (2021), and are designed to support shared understanding of environmental indicators rather than to operate as institutional limits.

WHO environmental guidelines are developed through structured reviews of international scientific literature. They synthesize findings from a wide range of studies to describe relationships between environmental factors—such as ambient air pollutants or environmental noise—and population-level observations reported in public health research. The resulting guideline values are framed for use at an aggregate level and are not intended for individual diagnosis, medical assessment, or personal risk interpretation.

Importantly, WHO guidelines do not carry legal or institutional status. They are not applied directly within national monitoring or reporting systems and do not establish enforceable requirements. Instead, they function as advisory reference values that provide a common point of comparison across different geographic and institutional contexts.

Common WHO guideline areas referenced in India

WHO guidance is frequently cited in discussions involving several environmental domains, including:

- Air quality, covering particulate matter (PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀) and selected gaseous pollutants

- Environmental noise, particularly in relation to long-term ambient exposure ranges

- Drinking water quality, encompassing a range of physical and chemical parameters

These guideline values are typically expressed as concentration levels or exposure ranges derived from global datasets and are not tailored to country-specific monitoring conditions or institutional frameworks.

Relationship Between WHO Guidelines and National Standards

WHO guidelines are designed to be broadly applicable across diverse environmental and socioeconomic settings. Their purpose is to summarize scientific assessment outcomes in a form that can inform international comparison and discussion. National standards, by contrast, are developed within specific institutional contexts and are structured around domestic monitoring and reporting systems.

For this reason, WHO guidelines are best understood as scientific reference tools rather than as substitutes for country-specific pollution standards. They contribute to global evidence synthesis and contextual understanding, while national standards define how environmental data is organized and reported within particular jurisdictions.

Recognizing this distinction provides essential context for examining differences between WHO guideline values and national pollution standards, such as those established in India.

CPCB vs WHO – Understanding the Differences Without Ranking

Comparisons between national pollution standards and international guideline values are common, but they are often made without sufficient contextual grounding. Understanding the differences between frameworks developed by India’s Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) and guideline values published by the World Health Organization (WHO) requires attention to purpose, scope, and institutional design, rather than numerical contrast alone.

CPCB standards and WHO guideline values are created to serve different functions. CPCB standards are structured to operate within India’s national monitoring and reporting systems, providing reference points that support consistent description of environmental data across regions. Their design reflects domestic institutional arrangements and the need for uniform categorization within official datasets.

WHO guideline values, by contrast, are developed as global scientific reference points. They are derived from reviews of international research and are intended to summarize findings reported across diverse geographic and environmental settings. These guideline values are not embedded within any single country’s monitoring framework and do not carry institutional status.

Because of these differing roles, numerical values may vary without implying that one framework is more accurate, protective, or appropriate than the other. Differences reflect how each framework is constructed and applied, rather than a hierarchy of correctness.

Limits of “Stricter” or “Looser” Comparisons

Pollution standards are sometimes described using simplified terms such as “stricter” or “weaker,” but such labels can obscure important contextual factors. Numerical values alone do not capture how standards are defined, interpreted, or reported within monitoring systems.

For example, comparisons based solely on numbers do not account for:

- Differences in averaging periods used to summarize measurements

- Variation in monitoring coverage across locations

- Distinct classification or reporting conventions

- Regional variation in environmental observation contexts

As a result, lower or higher numerical values cannot be interpreted in isolation. Standards function within broader descriptive systems that shape how environmental data is recorded and communicated.

Context Over Comparison

Both CPCB standards and WHO guideline values are periodically updated as scientific assessments, measurement techniques, and data availability evolve. However, they are shaped by different institutional objectives. National standards are designed to support structured reporting within a specific institutional environment, while international guidelines are intended to facilitate shared scientific reference across countries.

Pollution standards therefore vary according to geographic, institutional, and methodological context. Interpreting them requires attention to how each framework is designed to function, rather than reliance on direct numerical comparison.

Recognizing these distinctions helps readers move beyond surface-level contrasts and approach pollution data as structured reference information within monitoring systems, rather than as absolute measures of environmental quality or individual risk.

How These Standards Are Used in Everyday Reporting

Pollution standards most commonly appear in public discourse through summaries, dashboards, and periodic reports rather than through formal policy documents. When air quality, noise levels, or water conditions are reported, the figures presented are typically interpreted within existing institutional or guideline frameworks that shape how measurements are summarized and displayed.

Air quality reports and public dashboards

In India, air quality data collected through monitoring networks is often converted into indices or categorical summaries before being released publicly. This process involves applying standardized averaging periods and classification rules defined within national monitoring frameworks. institutional reference values associated with the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) provide the structure used to organize and present raw concentration data in a consistent format.

In parallel, international reporting or research summaries may reference World Health Organization (WHO) guideline values to provide broader comparative context. As a result, national reports and international comparisons may appear to differ in their numerical presentation, even when they are derived from the same underlying measurements. These differences reflect the use of distinct reference frameworks rather than inconsistencies in the data itself.

Noise and water quality reporting

Noise conditions are commonly reported using designated zone-based categories, such as residential or commercial classifications, rather than through continuous exposure tracking. Water quality reporting often aggregates multiple parameters into simplified status descriptors for surface waters or supply systems. In both cases, reporting emphasizes standardized description of observed conditions rather than interpretation of individual exposure.

Within India, many of the measurement methods and testing procedures that support such reporting are specified through institutional standards bodies, including the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS). These specifications contribute to consistency in how observations are recorded and summarized across different monitoring contexts.

Why numbers can appear confusing

Differences in reported figures often arise because reporting systems apply distinct reference conventions. Common sources of variation include:

- Use of different averaging periods

- Variation in monitoring coverage by location

- Application of institutional reference values versus international guideline values

As a result, the same environmental conditions may be described differently across platforms without being contradictory.

Understanding how pollution standards shape reporting conventions helps readers interpret published figures as contextual information within monitoring systems, rather than as definitive statements about environmental quality or individual outcomes.

Key Takeaways for Readers

- Pollution standards function as reference frameworks that structure how environmental data is monitored, summarized, and reported, rather than as tools for predicting individual outcomes.

- In India, standards developed by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) define how pollution measurements are classified, aggregated, and communicated within national monitoring systems.

- World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines serve a distinct role as global, science-based reference values derived from international research and do not carry legal or institutional status within individual countries.

- Differences between CPCB standards and WHO guideline values reflect variations in institutional context and design objectives, rather than simple rankings of quality, strictness, or effectiveness.

- Pollution figures presented in reports or dashboards are shaped by measurement methods, averaging conventions, and reporting frameworks, and should be understood within those descriptive contexts.

Taken together, these points underscore that pollution standards provide structured ways of interpreting environmental data. They support consistency and comparability within monitoring systems, rather than serving as absolute statements about environmental conditions or individual risk.

References

Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS)

Indian standards related to environmental measurement methods, including water quality parameters and noise limits.

https://www.bis.gov.in/

Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB)

National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS).

Official reference standards for ambient air pollution monitoring in India.

https://cpcb.nic.in/national-ambient-air-quality-standards/

Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC)

National environmental policy framework and institutional oversight for pollution regulation in India.

https://moef.gov.in/

World Health Organization (WHO)

WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines (2021).

Scientific reference values for ambient air pollutants based on international assessments.

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034228

World Health Organization (WHO)

Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region.

Reference ranges for long-term environmental noise exposure based on population-level research.

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789289053563

World Health Organization (WHO)

Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality.

Reference values for physical and chemical parameters used in water quality assessment.

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549950

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

Global environmental assessment, monitoring, and coordination reports.

https://www.unep.org/resources

Author Bio

Soumen Chakraborty is the founder of GreenGlobe25, an independent educational platform focused on environmental systems and pollution research in India. His work centers on explaining pollution-related concepts, standards, and institutional frameworks using publicly available data and authoritative sources.

Content published on GreenGlobe25 is written as neutral, research-based educational explainers. It draws on materials from organizations such as the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), the World Health Organization (WHO), and other institutional bodies, and follows a documented fact-checking and source-attribution process. The material is descriptive in nature and does not provide professional, medical, or policy advice.

Educational Context Note: This article explains institutional and scientific frameworks for pollution measurement and reporting. It does not provide personal health, safety, or compliance advice.